1. Procedure (Note 1)

2. Notes

1. Prior to performing each reaction, a thorough hazard analysis and risk assessment should be carried out with regard to each chemical substance and experimental operation on the scale planned and in the context of the laboratory where the procedures will be carried out. Guidelines for carrying out risk assessments and for analyzing the hazards associated with chemicals can be found in references such as Chapter 4 of "Prudent Practices in the Laboratory" (The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2011; the full text can be accessed free of charge at

https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12654/prudent-practices-in-the-laboratory-handling-and-management-of-chemical. See also "Identifying and Evaluating Hazards in Research Laboratories" (American Chemical Society, 2015) which is available via the associated website "Hazard Assessment in Research Laboratories" at

https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/about/governance/committees/chemicalsafety/hazard-assessment.html. In the case of this procedure, the risk assessment should include (but not necessarily be limited to) an evaluation of

4-phenylbutanoic acid,

dichloromethane,

DMF,

(COCl)2,

MeNHOH∙HCl,

NaHCO3,

TsCl,

Et3N,

MgBr2∙Et2O,

1,2-dichloroethane,

N-ethyldiisopropylamine, silica gel,

petroleum ether,

ethyl acetate, anhydrous

Na2SO4 as well as the proper procedures for working with UV-light sources. UV-C light (254 nm) is especially damaging to the eyes and skin. The lamps should never be turned on while the door to the photoreactor is open.

2.

4-Phenylbutanoic acid (>98%) was purchased from leyan.com Shanghai, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

4-phenylbutanoic acid (98%) purchased from BLD pharm.

3. The oven-dried single-necked flask (100-mL) should be weighed before setting up the reaction.

4. Anhydrous

dichloromethane was obtained from GHTECH Shantou, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

dichloromethane purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

5. Anhydrous

N,N-Dimethylformamide (

DMF, AR) was obtained from Macklin Shanghai, China, and was used as received.The checkers used

DMF purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

6.

Oxalyl chloride [

(COCl)2, 98%] was obtained from Energy-chemical.com Anqing, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

Oxalyl chloride (>98%) purchased from TCI.

7. On half-scale, the checkers obtained 0.90 g (99%) of product. The authors reported obtaining 1.82 g (99%) of product on full scale. Characterization data of

4-phenylbutanoyl chloride 2:

1H NMR

pdf (700 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.31 (t,

J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (t,

J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d,

J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.90 (t,

J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.69 (t,

J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.05 (p,

J = 7.4 Hz, 2H).

13C NMR

pdf (176 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 173.8, 140.5, 128.8, 128.6, 126.5, 46.4, 34.4, 26.7. IR (film): 3063, 3028, 2935, 2864, 1797, 1603, 1497, 1454, 1403, 1362,1166, 1084, 1054, 1030, 962, 929, 856, 819, 747, 719, 700, 682 cm

-1. GC-QTOF of

2 showed only the mass of the corresponding acid (

1): [M] calc'd for C

10H

12O

2: 164.0837. Found: 164.0830.

8.

MeNHOH∙HCl (>98%) was purchased from bidepharm.com Shanghai, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

MeNHOH∙HCl (97%) purchased from BLD pharm.

9.

NaHCO3 (>99.5%) was obtained from Macklin Chemical Shanghai, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

NaHCO3 (>99.5%) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

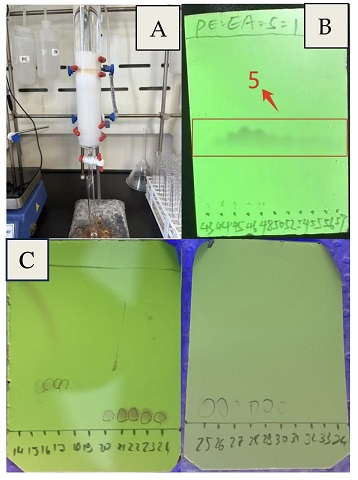

10. TLC (Figure 5) analysis was performed on silica gel plates (0.15-0.2 mm, glass-backed, which was purchased from Nuotai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Shanxi, China) with hexane:

ethyl acetate = 1:1 (v/v) as the eluent. The plate was visualized using a UV lamp (254 nm). The

N-hydroxy-N-methyl-4-phenylbutanamide 3: Rf = 0.37 (hexane:EA = 1:1, v/v).

Figure 5. TLC analysis by UV (eluent: PE: EA = 1:1, v/v) (photo provided by authors)

11. Anhydrous

Na2SO4 (>99%) was purchased from Tianjin ZhiYuan Reagent Co., Ltd, China, and used as received. The checkers used

Na2SO4 (>99.5%) purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

12. On half-scale, the checkers obtained 0.95 g of product. The authors reported obtaining 1.90 g of product on full scale.

13. To obtain an analytically pure sample of compound

3, roughly 450 mg of crude product was purified by flash column chromatography. A column (~2 cm diameter) was filled to 1/3 with

ethyl acetate/heptanes = 1:1. To this, 13 g of silica gel (suspended in 50 mL of the same solvent mixture) were added and pressure was applied using a hand pump to compress the silica gel and remove excess solvent. The crude material, further liquified by addition of 250 μL

dichloromethane, was transferred onto the silica gel. The flask, which had contained the crude mixture, was washed with additional 500 μL of

dichloromethane, which was also transferred onto the silica gel. The walls of the column were washed with solvent mixture (

ethyl acetate/heptanes = 1:1, 2 x 1 mL). After topping the silica gel with sand (1 cm), the column was filled with the same eluent mixture (110 mL) and collection of 12 mL fractions was started. Following elution of the first solvent portion, elution was continued with

ethyl acetate/heptanes = 6:4 (100 mL). The product eluted in fractions 6-14 (Figure 6) and these fractions were combined in a 250 mL round-bottom flask. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator (40 ℃, 660 to 20 mbar), followed by high vacuum (23 ℃, 10

-1 mbar), and the product was isolated as a colorless oil (361 mg, 1.87 mmol, 93% - assuming a 2 mmol scale). An Rf of 0.31 in

ethyl acetate/heptanes = 7:3 was determined.

Figure 6. TLC of collected fractions (eluent: EA/heptanes = 7:3 v/v); product was detected in fractions 6-14.

14. Characterization data of

N-hydroxy-N-methyl-4-phenylbutanamide 3:

1H NMR

pdf (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.50 (s, 1H), 7.29 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 3.27 (s, 3H), 2.68 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.54 - 2.25 (m, 2H), 2.08 - 1.93 (m, 2H).

13C NMR

pdf (151 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 167.2, 141.2, 128.6 (4C), 126.2, 35.8, 35.1, 30.1, 26.6. IR (film): 3164, 3086, 3064, 3027, 2924, 2861, 1604, 1496, 1453, 1390, 1196, 1113, 747, 699 cm

-1. [M-H] calc'd for C

11H

14NO

2-: 192.1030. Found: 192.1036. Determination of purity: 19.3 mg (0.100 mmol) of

N-hydroxy-N-methyl-4-phenylbutanamide (

3) and 16.6 mg (0.0987 mmol)

1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (>98%) were dissolved in CDCl

3. By qNMR

pdf analysis, the purity was determined to be 98.8%.

15.

p-Toluenesulfonyl chloride (

TsCl, >99%) was obtained from Energy Chemical Shanghai, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

p-toluenesulfonyl chloride purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

16.

Triethylamine (

Et3N, >99%) was obtained from aladdin-e.com Shanghai, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

triethylamine purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

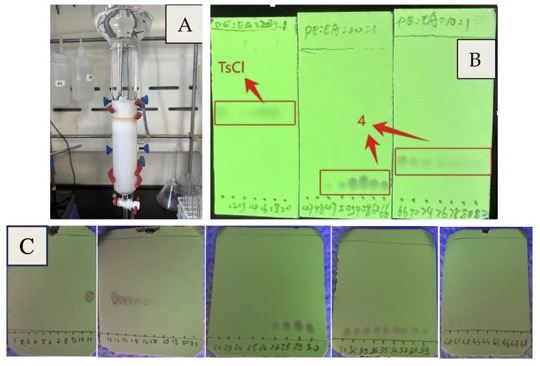

17. TLC (Figure 7A) analysis was performed on silica gel plates (TLC silica gel GF254, adhesive: sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, thickness: 0.15-0.2 mm, glass-backed, obtained from Nuotai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Shanxi, China) with

petroleum ether:

ethyl acetate = 10:1 (v/v) as an eluent. The plate was visualized using a UV lamp (254 nm).

N-Methyl-4-phenyl-N-(tosyloxy)butanamide 4: Rf = 0.25 (PE: EA = 10:1, v/v). The checkers employed an eluent system of heptanes/

ethyl acetate. TLC (Figure 7B) analysis was performed on silica gel plates (TLC aluminium sheets silica gel 60 with fluorescence indicator, thickness: 0.2 mm, obtained from Macherey-Nagel GmbH, Germany) with heptanes:

ethyl acetate = 10:1 (v/v). The plate was visualized using a UV lamp (254 nm).

N-Methyl-4-phenyl-N-(tosyloxy)butanamide 4: Rf = 0.17 (heptanes:

ethyl acetate = 10:1, v/v).

Figure 7. TLC analysis by UV (eluent: (A) PE: EA = 10:1, v/v; (B) heptanes: EA = 10:1, v/v) (photo provided by authors)

18. Flash column chromatography (Figure 8A) was performed on silica gel (230-400 mesh, purchased from Macherey-Nagel GmbH, Germany, and was used as received). A column with a 4.6 cm diameter x 25.4 cm height was dry-packed with 60 g of silica gel, and the column was compacted using a hand pump. The concentrated ca. 4 g crude product was dissolved in

dichloromethane (10 mL), which was then mixed with ca. 4 g dry silica gel for sample preparation by vacuum under reduced pressure (40 ℃, 600 mbar to 30 mbar). The uniformly mixed silica gel-containing sample was subsequently added to the compacted column. The column was gently tapped to ensure that the sample layer remained even. The top layer of silica gel was layered with

Na2SO4 to provide a buffering effect and prevent the silica gel from being washed away by eluent. The eluent (

petroleum ether:

ethyl acetate = 40:1, 410 mL - the checkers used heptanes instead of

petroleum ether) was then added to the top of the

Na2SO4, with fraction collection (tube size: 20 mL) beginning immediately. Then the eluent solvent system was switched to PE:

ethyl acetate = 20:1 (v/v, 420 mL), followed by PE:

ethyl acetate = 10:1 (v/v, 880 mL). The desired product was obtained in tubes 49-82 (Figure 8B, using heptanes:

ethyl acetate, the checkers detected product in fractions 59-99 using 1210 mL of eluent on full scale and in fractions 27-42 on half scale, Figure 8C). The combined solution containing the pure product was concentrated on a rotary evaporator (40 ℃, 600 mbar to 30 mbar) and dried in a high vacuum (ambient temperature (20 ℃), 1 × 10

-1 mbar) for 2 h.

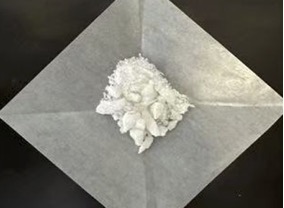

Figure 8. A. chromatography column; B. fraction collection (eluent: PE:EA = 20:1 and 10:1, v/v); C. Half-scale fraction collection with cuvettes (eluent: heptanes:EA = 10:1, v/v); product was detected in fractions 27-42 (photos A and B provided by authors and photo C provided by checkers)

19. On half-scale, the checkers obtained 1.60 g (92%) of product. The authors reported obtaining 3.16 g (91%) of product on full scale. Whereas the authors reported a colorless solid (

Figure 9), the compound did not solidify in the checkers' hands, and they obtained a colorless oil. Characterization data of

N-methyl-4-phenyl-N-(tosyloxy)butanamide 4:

1H NMR

pdf (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.82 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.14 (s, 3H), 2.50 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.46 (s, 3H), 2.20 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.79 (p, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H).

13C NMR

pdf (151 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 178.3, 146.9, 141.6, 130.8, 130.3, 129.5, 128.6, 128.5, 126.1, 38.4, 35.2, 32.1, 25.6, 22.0. IR (film): 3084, 3061, 3027, 3002, 2943, 2867, 1697, 1597, 1496, 1454,1380, 1295, 1212, 1194, 1180, 1118, 1090, 1030, 1019, 912, 867, 816, 801, 751,701, 688, 662, 630, 554 cm

-1. [M+H] calc'd for C

18H

22NO

4S

+: 348.1264. Found: 348.1261. Determination of purity: 34.4 mg (0.0990 mmol) of

N-methyl-4-phenyl-N-(tosyloxy)butanamide (

4) and 16.5 mg (0.0981 mmol)

1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (>98%) were dissolved in CDCl

3. By qNMR

pdf analysis, the purity was determined to be 99.3%.

Figure 9. Solid N-methyl-4-phenyl-N-(tosyloxy)butanamide (photo provided by authors)

20.

Magnesium bromide ethyl etherate (

MgBr2∙Et2O, 99%) was obtained from Energy-chemical.com Anqing, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

magnesium bromide ethyl etherate (99%) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

21.

1,2-Dichloroethane (anhydrous, water ≤ 50 ppm, 99.8%) was obtained from J&K Scientific, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

1,2-dichloroethane purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

22. The purchased

magnesium bromide ethyl etherate has many solid blocks, which need to be crushed into powder as much as possible, otherwise it may affect the reaction yield. For the authors' full-scale run and the checkers' half-scale run, a crushing time of 10 min was sufficient, whereas the checkers' full-scale run required sonication for 30 min to reach the desired consistency.

23.

N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 99%) was obtained from Macklin Shanghai, China, and was used as received. The checkers used

N,N-diisopropylethylamine (>98%) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

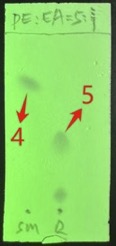

24. The reaction is monitored by TLC: Stirring is stopped to allow the solid to settle, and the reaction supernatant is taken for TLC analysis. TLC (Figure 10) analysis of the reaction mixture was performed on silica gel plates (TLC silica gel GF254, adhesive: sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, thickness: 0.15-0.2 mm, glass-backed, obtained from Nuotai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Shanxi, China) with

petroleum ether:

ethyl acetate = 5:1 (v/v) as an eluent. The plate was visualized using a UV lamp (254 nm). The

2-bromo-N-methyl-4-phenylbutanamide 5: Rf = 0.40 (PE: EA = 5:1, v/v). The checkers employed an eluent system of heptanes/

ethyl acetate. TLC analysis was performed on silica gel plates (TLC aluminium sheets silica gel 60 with fluorescence indicator, thickness: 0.2 mm, obtained from Macherey-Nagel GmbH, Germany) with heptanes:

ethyl acetate = 4:1 or 5:1 (v/v) as an eluent. The plate was visualized using a UV lamp (254 nm). The

N-methyl-4-phenyl-N-(tosyloxy)butanamide 4: Rf = 0.18 (heptanes:

ethyl acetate = 4:1, v/v) and 0.10 (heptanes:

ethyl acetate = 5:1, v/v - see Figure 11, below). If there is any residual starting material after 4 h, the reaction time can be extended to ensure complete conversion (in the checkers' case, the reaction was still found to be incomplete after 6 h, for which reason the reaction was continued overnight, resulting in a total reaction time of 16 h).

Figure 10. TLC analysis by UV (eluent: PE: EA = 5:1, v/v) (photo provided by authors)

25. Flash column chromatography (Figure 11A) was performed on silica gel (230-400 mesh, purchased from Macherey-Nagel GmbH, Germany, and was used as received). The column with a 4.6 cm diameter x 25.4 cm height was dry-packed with 45 g of silica gel, and the column was compacted using a hand pump. The concentrated ca. 4 g crude product was dissolved in

dichloromethane (10 mL), which was then mixed with ca. 4 g dry silica gel for sample preparation by vacuum under reduced pressure (40 ℃, 600 mbar to 30 mbar). The uniformly mixed silica gel-containing sample was subsequently added to the compacted column. The column was gently tapped to ensure that the sample layer remained even. The top layer of silica gel was layered with

Na2SO4 to provide a buffering effect and prevent the silica gel from being washed away by eluent. The eluent (PE:

ethyl acetate = 20:1, 315 mL - the checkers used heptanes instead of PE) was then added to the top of the

Na2SO4, with fraction collection (tube size: 20 mL) beginning immediately. Then eluent solvent system was switched to PE:

ethyl acetate = 10:1 (v/v, 220 mL), followed by PE:

ethyl acetate = 5:1 (v/v, 240 mL) and PE:

ethyl acetate = 2:1 (v/v, 450 mL). The desired product was obtained in tubes 44-56 (Figure 11B, using heptanes:

ethyl acetate, the checkers detected product in fractions 44-76 using 600 mL of eluent on full scale and in fractions 20-30 on half scale, Figure 11C). The solution containing the pure product was concentrated on a rotary evaporator (40 ℃, 600 mbar to 30 mbar) and dried in a high vacuum (ambient temperature (20 ℃), 1 × 10

-1 mbar) for 2 h.

Figure 11. Purification; A. chromatography column; B. fraction collection with cuvettes (eluent: PE: EA = 5:1, v/v); C. Half-scale fraction collection with cuvettes (eluent: heptanes:EA = 5:1, v/v); product was detected in fractions 20-30 (Photos A and B provided by authors and photo C provided by checkers)

26. On half-scale, the checkers obtained 0.98 g (87%) of product. The authors reported obtaining 2.07 g (91%, 97.5% purity) of product on full scale Characterization data of

2-bromo-N-methyl-4-phenylbutanamide 5:

1H NMR

pdf (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.31 - 7.27 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.23 - 7.18 (m, 3H), 6.39 (s, 1H), 4.27 (dd, J = 8.6, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 2.88 - 2.81 (m, 4H), 2.81 - 2.74 (m, 1H), 2.51 - 2.44 (m, 1H), 2.35 - 2.26 (m, 1H).

13C NMR

pdf (151 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 169.2, 140.1, 128.7, 128.7, 126.5, 51.4, 37.5, 33.3, 27.1. IR (film): 3286, 3086, 3027, 2939, 1653, 1560, 1496, 1454, 1411, 1159, 745, 699 cm

-1. [M + H] calc'd for C

11H

15BrNO

+: 256.0332. Found: 256.0330. M.p. = 86-88 ℃.

27. Determination of purity: 32.3 mg (0.126 mmol) of

N-methyl-4-phenyl-N-(tosyloxy)butanamide (

5) and 14.0 mg (0.0832 mmol)

1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (>98%) were dissolved in CDCl

3. By qNMR

pdf analysis, the purity was determined to be 99.0%.

3. Discussion

To rationalize this transformation, a soft enolization process was proposed. The hydroxamate ester 4 coordinates with magnesium bromide to afford intermediate A. In this complex, the C-H bond at the α-position of the carbonyl group is acidified, which can be deprotonated by a weak base, thereby leading to the formation of the enol intermediate B. Intermediate B undergoes spontaneous cyclization along with the cleavage of the weak N-OTs bond, resulting in an α-lactam C. Intermediate C further undergoes bromide nucleophilic ring-opening to produce intermediate D, which, after grabbing a proton, ultimately furnishes the amide product 5.

Scheme 1. Substrate scope and proposed reaction mechanism

Copyright © 1921-, Organic Syntheses, Inc. All Rights Reserved